- Home

- Allison Mills

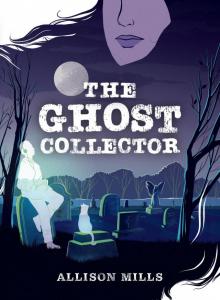

The Ghost Collector

The Ghost Collector Read online

For Louisa and Lois

1

Shelly’s grandma teaches her about ghosts, how to carry them in her hair. If you carry your ghosts in your hair, you can cut them off when you don’t need them anymore. Otherwise, ghosts cling to your skin, dig their fingers in under your ribs, and stay with you long, long after you want them gone.

Shelly’s mother doesn’t like ghosts. She doesn’t like Grandma telling Shelly about them. It’s an old argument, one they have every time Grandma gives Shelly a lesson. “You’ll scare her,” she says, like Shelly isn’t in the room. “You’ll keep her up at night.”

“How is she going to take care of herself if she can’t take care of the dead?” Grandma asks, and Shelly’s mother never has much of an answer for that. So Grandma teaches Shelly about ghosts, how to keep them, and how to get rid of them—not just her own ghosts but other people’s, too. Shelly likes to think of herself as her grandma’s apprentice.

Today, Grandma’s client is a woman clad in expensive yoga pants with her hair in a high ponytail. “We burned sage,” the woman says. She tours Shelly and Grandma around her haunted apartment—it’s bright and airy, much bigger than the old duplex Shelly and her mom and grandma share. “To cleanse it, you know?”

Grandma smiles, all bland and pointed, and Shelly stifles a laugh with her hand at the image of this yoga lady waving her spice rack around, trying to exorcise her apartment. “To cleanse it?”

“From the . . . spirits. The demons. You know.” The woman gestures vaguely at Grandma, at her soft brown skin and warm brown eyes, at the little turtle earrings she wears every day. The things that make some people say Native, but Grandma corrects them and says Ililiw or Cree. “It’s cleansing. The smoke. We fanned it around the whole house and nothing. The spirits are still here.”

Shelly can see the ghost that haunts the lady’s apartment dancing around her feet. It’s a little dog with a constantly wagging tail, trotting around on tiny paws with nails that clack against the hardwood floors and echo through the hallways. It noses its way over to Shelly and Grandma like it wants to play.

Grandma keeps smiling, her eyes on the woman and not the ghost dog. “I don’t use sage to cleanse ghosts.”

“Oh. So it’s like . . . for other stuff? Bad juju?”

Grandma turns her back on the woman. “This is a tough case,” she says and winks at Shelly. “I might have to charge a little more for the work. Do you mind?”

Grandma heads deeper into the apartment, listening to the woman talk seriously about the sound of claws scraping over the floors and the cold wind that blows around her ankles whenever she comes home—about how she feels like the spirits want her gone, and isn’t it weird that her brand-new condo is haunted like this?

Shelly takes a seat in the hallway and clucks her tongue at the dog, smiling. She’s never had a pet before—too expensive—but she likes dogs. A ghost dog would be a good pet—ghosts don’t need feeding the same way living beings do.

“It’s okay,” she tells the dog, leaning toward it so Grandma’s client won’t hear her whispering. She tugs the tie off the end of the braid Grandma wove her long, dark hair into and combs her fingers through it, loosening it. “Grandma and I are going to take you for a walk.”

The dog’s tail wags even harder and Shelly lets it dance around her, nipping at the ends of her hair as she waits for Grandma to finish talking to the woman about the monster she imagines is hiding under her bed.

People are always coming by the house to see if Grandma will get rid of their ghosts—cats that wind around their ankles and trip them when they walk. Dogs that bark in the middle of the night, startling them out of sleep.

Shelly catches the dog in the ends of her hair then scoops it into her arms when Grandma and the woman come back into the hallway, scratching it under the chin. Holding it is like holding a cold wind, and when the puppy licks her face it feels like someone is rubbing an icicle against her cheek.

“Will this take long?” the lady asks, getting her wallet out of her purse. “Is $300 enough?”

Three hundred is a lot for a ghost. Most of Grandma’s clients pay in knickknacks and favors and food. Grandma doesn’t normally charge much because if people know they have a ghost, they might pay anything to get rid of them—do anything.

“Not long at all,” Grandma promises. “We’ll be out of here before you know it.”

They walk the dog to the park, and Shelly and the dog play fetch with an invisible stick until the dog fades away, finally ready to rest.

They go home and Shelly helps Grandma out of her coat. Shelly’s mother is in the kitchen and there’s a frozen lasagna in the oven.

“You’ve got to be responsible,” Grandma tells Shelly. “You can’t charge people through the nose to get rid of a ghost.”

Mom looks over from putting her hair up to go to work, her uniform shirt all nicely pressed. Her hair is long, like Grandma’s and Shelly’s, but she almost never wears it down outside the house. She doesn’t want anything clinging to it.

“I made dinner for you and Shelly.” Mom points a finger at Grandma as the oven timer goes off. “You could charge a little more.”

“We’ve got to undercut the frauds so people come to us instead. We can help people,” Grandma says, pulling the lasagna out of the oven. “Sit and eat before you go.”

“Someone has to pay the bills,” Mom says, but she sits and cuts up the lasagna in its tinfoil pan. “What about helping us?”

The duplex they rent isn’t anything like the fancy apartment Shelly and Grandma spent the afternoon in. The floors creak when it’s cold and the front door opens right into the kitchen because there’s no space wasted. The cabinets are sturdy wood but old, and every room has orange wallpaper Shelly’s mother hates but can’t change because they’re renting. She did cover Shelly’s walls with posters of cats and dogs and other pets Shelly likes but can’t have to help make the room look nicer, though.

Shelly’s bedroom is the smallest one. With her dresser shoved into the doorless closet, there’s enough room for her bed and a bookshelf but not much else, especially since she tends to leave her clothes on the floor—clean things folded and stacked neatly, dirty clothes in a heap in the corner—instead of putting them away where they belong. The only thing Shelly puts away is a sweater, blue with an orange cat on the front. Shelly and her mom found it brand-new at the thrift store and it always goes in a drawer because it’s Shelly’s favorite. The room feels softer and more lived in around the edges with clothes everywhere—more comfortable.

Grandma grabs her purse as she sits at the table, pulling out the money she and Shelly made for the ghost dog. “Is this useful?”

Mom looks surprised. “For just one ghost?”

“The lady was rude,” Shelly says, leaning over to scoop noodles from the pan and onto her plate. “She talked about burning sage to cleanse the spirits from her home, but it was just a little dog.”

Mom laughs, setting the cash down on the table. “One of those clients,” she says. “You need to get more rich people who don’t know anything about the dead—this is the kind of money we need around here.”

“It was a one-time thing,” Grandma says, shaking her head. “I don’t want to seem like some kind of fraud.”

“You go around telling people you can clear out ghosts. You already seem like a fraud.” Mom serves Grandma some lasagna then serves herself. “If you don’t want rude women with small dogs making assumptions about you, maybe don’t offer to be the brown woman they bring in to spiritually clean their house.”

Grandma frowns at Mom. “We’re not a stereotype.”

“Mom, you’re a bit of a stereotype.”

“It was a cute dog,” Shelly says loudly. “A ghost dog would make a good pet, don’t you think? You wouldn’t have to buy food or take it to the vet.”

Mom and Grandma both turn to look at her.

“You can’t keep ghosts hanging around like that,” Grandma says. “Everyone has to move on eventually—maybe in their own time, but it’s not fair to hold someone captive.”

“She knows, Mom,” Shelly’s mother said, plainly amused. “While I support a pet that costs no money, you’re around death more than enough as it is, Shell. Nobody in this house needs haunting. The dead are dead, and that’s the way it should be. Leave them alone.”

“They’re dead, but sometimes they need help passing over,” Grandma says. “Then we’ve got a responsibility to help them move on.”

That’s how it is most of the time. Mom worries about money and whether Shelly will get nightmares. Grandma keeps calm and steady—more sure of herself than anyone else Shelly knows.

2

Shelly is the only person in the sixth grade who knows, deep in her bones, that ghosts exist. She knows that because Ms. Flores assigns the class a presentation about what they want to be when they grow up—a teacher or an actor or a chef—and drops them off at the school library with Mrs. Hogan, the librarian, to do research.

“My dad’s a professor, so I’m going to write about being a physicist,” Isabel says, while she and Shelly are searching the non-fiction section for books. Isabel and Shelly aren’t friends, exactly, but their desks are beside each other and Shelly likes Isabel. She’s Korean and wears her long, dark hair loose like she’s not afraid of what might get caught in it. Isabel dresses in bright colors and always has new clothes. She’s nice though—some of the other kids single Shelly out for being brown, for being the only Indigenous kid in their class. Isabel doesn’t. Isabel tells them to knock it off. “I don’t really need a research book to write about it.”

“My grandma is a ghost hunter,” Shelly says. “I’m going to be one, too.”

Isabel gives Shelly a skeptical look. “Ghosts don’t exist. My dad’s a scientist. I think he’d know if ghosts were real. Someone serious would be studying them.”

“They do. I’ve seen them. Grandma takes me with her on jobs sometimes.” Shelly knows people don’t always believe they’re being haunted, but it’s the truth. Ghosts are as real as she and Isabel are.

“They don’t,” says a voice behind her, and Shelly turns to see Lucas, the tallest kid in fifth grade, with a book on forensics tucked under his arm. “Ghosts are made up.”

Shelly’s used to people not believing in ghosts, but it’s still frustrating to have people argue with her when she knows they’re real. She shakes her head. “I’ve talked to plenty of ghosts before.”

“You haven’t because they’re not real.” Lucas holds up the book in his hands. “Show me proof of ghosts if you want me to believe you.”

“Did everyone find what they were looking for?” Mrs. Hogan asks, looming out of the stacks. She looks at them like she knows they were arguing.

“Yes,” says Lucas.

“I have a book,” says Isabel.

Shelly wishes she’d picked something up right away, but she’s not sure the library has anything she could use. “I haven’t found one yet.”

Mrs. Hogan turns her attention to Shelly. “Shelly, can I talk to you for a moment? You’ve still got lots of time to find your book.”

Shelly knows where this is going. Mrs. Hogan doesn’t believe in ghosts either. “Yes, Mrs. Hogan.”

Shelly follows her across the library to the small circulation desk. Mrs. Hogan turns to her, expression disapproving. “I know you mean well, and your grandma works as a . . . psychic, Shelly, but you really shouldn’t go around telling your classmates ghost stories,” she says. “You might give them nightmares.”

Adults will sometimes believe Grandma when she talks about ghosts and hauntings, but they never believe Shelly. They’re like her mom—always more worried about bad dreams than the dead. Not everyone can see ghosts, even when they see the evidence of their presence. People look at Shelly and think she must be making up stories, especially adults. Especially teachers.

When Grandma talks about ghosts, people are more likely to listen. They don’t roll their eyes at her or tell her she’s making up stories to give people bad dreams. Grandma’s got age on her side. Even if people decide they don’t believe her after all, they let her finish speaking.

Most people think the dead are just gone, that they vanish with no transition period. Most people don’t ever get a chance to see ghosts the way Shelly and her grandma and mom can—even if her mom just works at the drugstore instead of busting ghosts with Grandma.

It’s a gift that runs in the family, like their dark hair and long noses and big brown eyes—women can see ghosts. Grandma’s mother could see ghosts, and her mother’s mother could, too. Grandma tells stories sometimes about when she lived up north, before she got married and moved down to the city with her white husband, who became her ex-husband. People would knock on her mother’s door and ask for help making sure their loved ones had moved on. Everyone knew she had a knack for speaking with the dead, even if they didn’t know exactly how she did it. Shelly wants that, too. Growing up in the city instead of up north, Shelly feels like she only gets bits and pieces of what it means to be Cree. Her mom talks politics, but that’s only one part of it, and other than her family the only Indigenous people Shelly knows are their neighbors. Ghost hunting is a way to connect with the people who came before her. It’s got history, the same way ghosts do.

Grandma’s mother never charged anything for her services, but times have changed and Grandma and Mom need to pay rent.

“I wasn’t saying anything scary.” Shelly does her best not to frown at Mrs. Hogan. “I was just talking about ghosts. Isabel’s dad is a professor so she’s writing about being a professor. My grandma hunts ghosts, so I’m going to write about being a ghost hunter.”

Mrs. Hogan doesn’t look like she believes Shelly, but she doesn’t say no to her idea either. “We have a few books on parapsychology,” she says. “And some on spiritualism and debunking urban legends. They might be a good place for you to start your research. Do you want me to help you find them in the catalog?”

Shelly lets Mrs. Hogan show her where to find the books. It’s easier than arguing. People at school are weird about ghosts. They don’t take her seriously. It’s obvious that Mrs. Hogan thinks ghost hunting is like one of the TV shows Grandma scoffs at, where a bunch of people run around old hospitals with infrared cameras in the dark and scare themselves. That’s not how Grandma works. She finds ghosts that need help and she helps them. No special equipment required.

Shelly sits down at her assigned table at the end of the library while they wait for Ms. Flores to come walk them back down the hall, and Lucas gives her books a judgmental look. “That’s all made up,” he says.

“The library doesn’t have any books on real ghosts,” Shelly says. “It’s passed down in my family.”

“So it’s made up.” Lucas is smug. “I knew it.”

Shelly frowns at him. “It’s not made up just because you don’t know about it and nobody wrote about it in a book. You don’t know everything.”

“Lucas. Shelly.” Mrs. Hogan stops beside their table. “Do I need to tell Ms. Flores you were arguing in class?”

Lucas sits up straighter in his chair. “No, Mrs. Hogan.”

Shelly wants to say Lucas started it, but Mrs. Hogan already pulled her aside once today. “Sorry,” she says. “We’ll stop.”

Shelly knows she’s right and that will have to be enough.

• • •

Shelly’s mother picks her up from school in her old, beat-up car. Its windshield is cracked and the radio always

sounds staticky because the antenna is broken. The rearview mirror is held in place with glue and hope. Her mom’s hair is up in a messy ponytail and she’s dressed for work, shirt rumpled after her shift. She looks tired. “How was school?” she asks, smiling. “Learn anything exciting?”

“We’re doing a project on what we want to be when we grow up,” Shelly says, climbing into the car and dropping her red backpack on the floor. It’s about as shabby as the car because she got it secondhand. Most of her clothes come from the thrift store, another thing that makes Shelly different from other kids. “Nobody believes in ghosts.”

“Oh no, Shelly—you told your teachers you wanted to be like Grandma?” Her mom looks both exasperated and amused. “Shell, you know people don’t like thinking about ghosts. I don’t like thinking about ghosts and I grew up with your grandma.”

“Why not?” Shelly asks. “There’s nothing wrong with ghosts.”

“They’re dead,” her mom says. “They’re dead and we’re alive. Those are two very different things. To everyone else it sounds like superstition.”

“Mrs. Hogan said I shouldn’t talk about ghosts in class or I’d scare the other kids.” Shelly doesn’t think that’s true. Isabel and Lucas didn’t believe her, but they weren’t afraid. Besides, what Shelly’s learning from her Grandma is more important than making friends at school. The dead don’t care how new your shoes are or what kind of job your parents have.

“Mrs. Hogan isn’t wrong. I had bad dreams about ghosts all the time when I was a kid.” Her mom turns the car on and pulls away from the curb. “I knew they were real. I think not knowing for certain would be even scarier.”

“Why were you scared?” Shelly asks because it baffles her—ghosts are just a part of life. “Ghosts are just people.”

Her mom is quiet for a moment, either thinking or concentrating on the road. “Ghosts aren’t just people,” she says. “I mean, they are, but they’re more than that—they’re people plus. They’ve been through everything you and I are ever going to go through, you know? They went through their whole lives and something kept them here even though they should’ve moved on to whatever comes next. Your grandma gets rid of ghosts because they’re out of step with the rest of the world.” She glances at Shelly. “I wouldn’t wish that on my worst enemy.

The Ghost Collector

The Ghost Collector