- Home

- Allison Mills

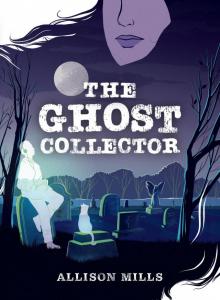

The Ghost Collector Page 2

The Ghost Collector Read online

Page 2

“People are afraid of ghosts because they know more than we do. They know what it feels like to live their whole lives and now they’re hanging in between here and the other side—not in one place or the other.” She shrugs. “I can’t blame people for not wanting to think about being trapped like that.”

“If someone can see you and talk to you, are you trapped?” Shelly asks. “We can see ghosts.”

“Sure,” says her mom, “but sometimes you might want to talk to someone else and you couldn’t. I mean, I’d never get tired of talking to you, Shell, but you might get tired of talking to me, don’t you think?”

Shelly looks at her mother and grins. “Yeah, I would,” she agrees. “I’d get bored. You’d have to let me have a pet then.”

Her mom laughs, and that’s the end of the ghost talk, but Shelly can’t help thinking that she’s wrong. Ghosts aren’t scary at all.

3

When they pull into their gravel driveway, Mrs. Potts is waiting by her front door. She lives in the other half of their duplex with just her two cats. Shelly’s pretty sure she and Grandma are about the same age, but Mrs. Potts wears a lot of cardigans with seasonal embellishments and keeps her gray hair short and in curls. It makes her seem older.

That and the cats.

“Hi!” Mrs. Potts says, as they get out of the car. Her cardigan today is black with orange and yellow felt leaves stitched to its front. Even looking at it makes Shelly feel itchy. “Amanda, I was just heading over to say hello to your mom.”

“I’m sure she’ll be happy for the visit, Edna,” Shelly’s mom says, with a look on her face that says, Oh no, we’re trapped. Mrs. Potts is very good at talking. Her daughter is a police officer and visits at least once a week—Mrs. Potts likes to brag about her. “I could go grab her.”

“Oh, no trouble,” says Mrs. Potts. “I’m on my way out the door, but I wanted to invite you for dinner tonight. Jenny’s coming over and I’m going to roast a chicken. There’ll be more than enough food for the two of us. I thought it might be nice.”

“Oh,” says Shelly’s mom, who doesn’t really like cats or Mrs. Potts very much. “I don’t know, we wouldn’t want to intrude . . .”

Mrs. Potts shakes her head. “Nonsense. I’d love the company.”

Shelly’s mother looks annoyed, but not enough to say no. “Thank you, Edna,” she says. “Can we bring anything? Dessert?”

“Dessert would be lovely,” Mrs. Potts says, smiling. “Come over around five.”

Shelly’s mom waits for Mrs. Potts to go back inside then looks down at Shelly. “Okay, well, I’m going to go buy a pie at the grocery store,” she says. “Tell Grandma we got ambushed and I’ll be home in half an hour.”

“Sorry, Mom,” Shelly says, grinning up at her. Going to Mrs. Potts’s house isn’t too bad—she gets to play with the cats. “Apple?”

“Apple,” Mom agrees.

• • •

Jenny Potts answers the door when they knock. Her short hair is a brown so dark it almost looks black, and she’s dressed in jeans and a T-shirt, not like a cop at all. Shelly’s not used to seeing her in anything but her uniform. “I’m sorry about this,” she says, stepping aside so they can enter. “Mom’s got a bee in her bonnet.”

“I don’t have a bee in my bonnet, I have ghosts in my house!”

Shelly’s mother, carrying a pie from the nice grocery store, the one that bakes things from scratch, looks immediately and thoroughly unimpressed. “Ghosts.”

“I told her she should just talk to your mom if she’s worried she’s being haunted, but . . .” Jenny shrugs. “She wanted to have you over for dinner.”

Grandma laughs and pushes past Jenny into the house. “Edna, let’s see what we can do,” she says. “It might just be the cats.”

“I can tell the difference between a cat and a ghost,” Mrs. Potts says. “I might not talk to spirits, but I know my cats.”

“Can I help?” Shelly asks, looking up at her mom. Normally she’d just do it, but with her mother there, asking seems important.

Mom hesitates but nods. “You can help.” She looks at Jenny. “It’ll be something small, if it’s anything.”

“Drinks?” Jenny suggests. “While they do ghost things?”

“Please,” says Shelly’s mom.

Mrs. Potts’s duplex is a mirror of their own. Shelly follows Grandma and Mrs. Potts through the kitchen and down the hallway. Mrs. Potts uses the big room—the one Shelly’s mom uses for a bedroom—as a living room. The cats are curled up together on the couch, and Shelly can hear the ghosts under the floor as soon as she steps inside the room.

“Oh,” she says. “It’s mice.”

“Mice?” Mrs. Potts repeats, alarmed. “Louisa, I promise you I don’t have mice. The cats hunt anything that tries to get in.”

“No, Edna, ghost mice,” says Grandma. “Your cats are probably the reason you’re having an issue. They’re doing too good a job.”

Mrs. Potts relaxes a bit, walking over to give one of the cats a pat. “They do like to bring me back presents.”

Shelly can see why her mom isn’t a big fan of cats. Ghosts are one thing—dead mice are another. “It sounds like they’re in the floor,” Shelly says, sitting down on the rug and knocking on it. A skittering sound under the floorboards makes Mrs. Potts shiver. Mice shouldn’t be hard to get rid of, but Shelly’s never had to get ghosts out of a floor before.

Grandma reaches up to undo her braided hair and lets it fall out, loose and free. “What do you think about the air vents?” she asks Shelly. “I think they could work.”

Animal ghosts tend to be simple—the spirits of creatures that haven’t realized they’re dead yet. Being outside helps them fade away because a ghost removed from an anchor—whether that’s its home, where it died, a favorite place, or a grave—will start to fade unless someone tries to keep it around. The dead aren’t made to stick around in the world of the living forever, although some ghosts are stronger than others, more concrete and settled in their death.

Shelly and her grandma use their hair like a net, like a fishing lure. They let ghosts cling to them and act as a hook to carry the dead to new places, places where they won’t be tied to anything and will be able to fade. Sometimes they offer comfort—they burn sweetgrass and feed ghosts warm milk—and sometimes they just let a spirit fade, let it travel to where it’s going because it doesn’t need much more than a nudge to carry on.

Shelly doesn’t really want to stick her hair down an air vent and hope it gets full of mice, but the vents are in the floor and Grandma is old.

“Vents might work,” she says. “I can do it.”

“Your mother is going to kill me,” says Grandma. “Then she’s going to regret killing me when I come back to haunt her.”

Shelly laughs and undoes her ponytail, scooting across the rug to the nearest vent. She carefully lowers her hair down through the grate and then looks up at Grandma and Mrs. Potts. “Do I just sit and wait?” she asks. “How many mice do you think—”

“Shelly!” Shelly turns her head, looking at her mom standing in the doorway of the room with Jenny. “What are you doing? Mom, what?”

“It’s mice,” says Shelly, trying not to frown. She knows what she’s doing. She’s carried around bigger ghosts than mice before. “I’m just getting them out.”

“Your hair is going to be full of ghosts and cat hair. Shell, pull back please. There’s got to be another way.”

“I was going to do it myself,” Grandma says. “Shelly wanted to try.”

“You shouldn’t be sticking your hair down vents either, Mom,” Shelly’s mother says. “This is a bad plan.”

Shelly feels a tug on the ends of her hair—one tug, followed by a bunch more all at once. She lifts her head up carefully and the ghosts come out with her, passing easily through the grat

e. Ghosts are spirits and spirits don’t care about things like barriers unless they want to care about them. Ghosts can touch people and things, but people and things can’t touch ghosts—not unless they’re like Shelly and her family.

Shelly lifts her head up with her hair full of little wisps of ghost mice, and her mother, across the room, shudders and looks away. “Mom, please—help Shelly outside?”

“They’re just mice,” Grandma says, amused. “Come on, Shelly. Let’s get rid of them.”

Grandma and Shelly walk out of the house, Shelly’s hair writhing with little ghost mice, and Grandma opens the front door so Shelly can step into the yard and comb out her hair with her fingers. It feels good doing the whole job start to finish on her own, especially with her mother there. Usually Shelly watches or just gets to help out a little, but this time it was all her.

“Those cats earn their keep,” Grandma says, as the ghosts scamper into the bushes lining the driveway. “Come on, Shelly. Let’s go show your mom the mice are gone.”

When they walk back into the living room, Shelly’s mom is sitting as far away from the vent in the floor as possible with a cat in her lap.

“All gone,” Shelly says. “No more ghosts in your floor, Mrs. Potts.”

“Thank you,” Mrs. Potts says. “Let me get you some money.”

“Oh no,” says Grandma. “Edna, don’t worry about it. We’re friends and you’re feeding us dinner. That’s more than enough.”

Mom glances up, briefly, at the ceiling then looks at Shelly as she takes a seat beside her. Shelly’s worried she’ll be mad, but she smiles.

“Extra pie for you tonight,” she says. “When you fill your hair with dust and mice for your neighbor, you get a big slice and as much ice cream on the side as you want.”

Shelly can’t help hoping that maybe this means her mom’s coming around to seeing things her way—seeing that Shelly isn’t just a kid and should be allowed to work with Grandma in the field. She smiles back at her mom. “Really?”

“Really,” Mom says, reaching out to give the ends of Shelly’s hair a playful tug. “You do have to wash your hair when we get home, though. I can see cat hair in it from here.”

4

Grandma doesn’t get rid of every ghost she comes across. She says sometimes ghosts deserve to do their haunting. And sometimes people deserve to be haunted.

“You don’t take ghosts from a graveyard,” Grandma says, braiding Shelly’s hair so she won’t catch any ghosts she doesn’t want. “Not unless they want to go, and then you can let them out. Most of those ghosts will leave if they really want to. Same with sacred places, churches and temples. Any ghosts doing their haunting there deserve to stay.”

Shelly rolls her eyes. “I know,” she says. “Sometimes it’s the living who make trouble for the dead.”

Grandma snorts, tugging playfully on the end of Shelly’s braid. “It’s good to know you’ve been listening.”

One of the first places Grandma took Shelly for ghost lessons was a graveyard—an old one where nobody had been buried for years. It was tucked in a small lot between a strip mall and a block of townhouses and kept tidy by the city. There was a ghost there, a faint shade of a person slowly transitioning from ghost to gone.

“Not everyone can see the dead,” Grandma said, pointing to the blurry shape propped up against the chain-link fence. “We can, and that means we’ve got responsibilities.”

Shelly was six and so excited about seeing the ghost she could hardly sleep. Mom decided that meant she was scared, but she wasn’t. Even then, she liked the dead.

The graveyard Grandma takes Shelly to this time is a 27-minute bus ride away. It’s a modern one—big, with tidy rows of tasteful headstones and brass plaques set in the ground. Shelly keeps to the path so she doesn’t walk on anybody’s grave.

“This kind of graveyard, you aren’t going to find a lot of ghosts,” Grandma says, leading Shelly toward the outer limits of the graveyard to the cheaper graves. “Lots of old ladies like me with nothing left to haunt about.”

On the outskirts of the graveyard are small graves with tiny aluminum stakes and rusted old plaques instead of proper headstones. They’re the cheap seats of burial places for people who can’t afford or aren’t willing to pay for a big headstone get buried. The graves are closer together and weeds sprout up between them. There’s a ghost there, a teenaged boy, sitting on a small grave, playing with a black plastic box that looks almost like a radio.

He looks up at Grandma and Shelly with eyes like black holes.

“Hello, Joseph,” Grandma says, sticking a hand in her purse and pulling out a stack of old cassette tapes. Shelly’s mom has a tape deck in her car, but these days tapes are all of old music and hard to find. Grandma puts them on the grave in front of the boy and he smiles at her.

“Old Lady,” he says. His mouth moves, but his voice comes from the headphones around his neck. He pops open his ghostly radio-like box and inserts the tapes one by one right after each other. They disappear as they slide into place, dissolving into the player. Ghosts don’t usually come with accessories—Joseph having the player and headphones means he was buried with them. “You want to know who’s roaming around the yard?”

“First I want to introduce you to my granddaughter,” Grandma says. “Joseph, this is Shelly.”

Joseph turns his unsettling eyes on Shelly. She does her best not to take a step back. After a moment, she bows to him, just a quick up-and-down bob, because she’s not sure what else to do when he’s staring like that.

Joseph laughs. “I like her,” he says. “Old Lady never introduced me to anyone before, Little Shell. You must be special. You ever heard of The Cure?”

Shelly shakes her head.

Joseph opens his box again and reaches inside. His hand slips down, down, all the way to his elbow as he digs around inside, and he pulls out a cassette and holds it out to Shelly. “They’re my favorite band. This is a good tape,” he says. “My favorite album. Take care of it for me.”

Shelly takes the tape. The faded lettering on it reads Disintegration. It’s so icy cold that touching it feels like being burned, but Grandma taught her how to accept gifts from the dead. When they give you something, you have to be grateful. You smile, say thank you, and take good care of it.

“Thank you,” Shelly says. “Do you want me to bring it back?”

“Nah,” Joseph says. “You keep that one for you. I got it memorized. Old Lady here brings me new stuff to listen to all the time.”

Shelly slips the tape into her pocket. Joseph isn’t as old as most ghosts she’s met. She wonders about that, but another thing about ghosts is that it’s rude to ask how they died. Most of the time Shelly and Grandma don’t even ask ghosts why they’re still hanging around when they meet them. Most of the time ghosts don’t even know they’re ghosts.

Joseph does. He sits on his grave and hums as music starts playing from his headphones. It sounds angry to Shelly—angry and sad. Joseph smiles like he likes it.

“What is that?” Shelly asks, pointing to the box. “It plays tapes?”

“It’s a tape deck,” Joseph says, his voice filled with pride echoing between the notes of the song. “It’s top of the line—the best portable tape deck money can buy. Always wanted one of these when I was alive. This tape was a good choice, Old Lady. You’ve got depths.”

Grandma laughs and takes a seat across from Joseph. She pats the grass beside her for Shelly to sit, too. “I like to think so. You said something about people roaming?”

Joseph makes a face. “Always business,” he says. “Yeah, we got some new ghosts. John Francis German over on the north side is confused. Doesn’t want to talk much. Estelle K. J. Park called me a punk kid and told me to get off her lawn.”

Shelly can’t help the laugh that bubbles out of her.

Joseph turns to her, sm

iling. “Little Shell gets me. Old Lady never laughs at my jokes.”

“I’ll laugh at your jokes when you get funnier,” Grandma says. “Do you think they want to move on? Do you think they need help?”

Joseph shrugs. “They don’t seem to like it here much.”

They talk to John Francis German first. He’s old, but not old-old—in between Shelly’s mom and grandma in age. He’s dressed in khakis and a polo shirt. He flickers in and out of focus as he wanders the north side of the graveyard, looking around like he’s lost.

He smiles when they get his attention.

“Hello,” he says politely. “I’m sorry. Could you give me directions? I’m not sure where I am.”

“Oh yes,” Grandma says, as she lets her hair out of its braid to catch him. “We can show you where you need to go.”

John comes with them to find Estelle K. J. Park. She isn’t as nice.

“Do you know how much I paid to be here?” Estelle asks, her voice croaky like a frog’s. She’s wearing a fuzzy bathrobe and big slippers. The lenses of her glasses are fogged over and Shelly can’t see her eyes. “I’ve got a big headstone coming. I ordered one with an angel on it—life-size. I’m not going anywhere until I see my angel.”

Estelle turns her back to them and John bends down close to Shelly and whispers, “I don’t think she’s lost.”

Shelly suppresses a laugh. Estelle doesn’t seem like the kind of ghost who’d like being laughed at.

“No,” Grandma agrees, matching John’s tone. “She’s exactly where she wants to be.”

“Darn tootin’,” says Estelle. “I know where I’m going, make no mistake. I didn’t take orders from anyone when I was alive and I’m certainly not going to start now I’m dead. I’ll move along in my own time.”

The Ghost Collector

The Ghost Collector